#1 of 3

American Ceramics,

Volume 8, #4, solo exhibition , Allrich Gallery, San Francisco, CA

Maria Porges,“Dan Snyder”

Dan Snyder’s graceful figures are clearly meant to evoke the past. Assembled on armatures from mold-formed fragments, these nymphs, angels, and caryatids look like recent archaeological discoveries from some ancient civilization, lovingly reconstructed into their present form from little more than shards. The softened, generalized, almost anonymous features, and amputated limbs of these mostly female figures emphasize such a reading as well. At the same time, Snyder’s formal strategies locate his work in the present, as part of a living tradition of modernistic figuration that traces its roots to Giacometti and Degas. Snyder’s work, however, is set apart from that of his teachers and older contemporaries by both his techniques and by an emphasis on the mutable nature and unique properties of clay.

In Seek-No-Further, the turning body of the angel looks almost as though it is ready to break away from its rocky pediment and become pure spirit. Snyder’s method of assembling the figure out of a shell of fragments often creates an astonishing “lightness of being.” At the same time, the whorl of vigorously modeled fragments out of which the angel emerges suggests clay’s original state. The spirit lives forever, Snyder implies, even though the flesh does not.

By returning to “mortal” clay after several years of working with polychrome steel, in more pop idiom, Snyder has come full circle in his work. Although these beautiful, decorated and frankly romanticized figures recall his earliest pieces, Snyder’s maturity gives this body of work a new strength and intelligence. By both drawing on the past and placing his work firmly in the context of the present, Snyder has brought his pieces into the dialogue about mortality and the body, which presently occupies the art world.

#2 of 3

Ceramic Monthly

"Old Roses"

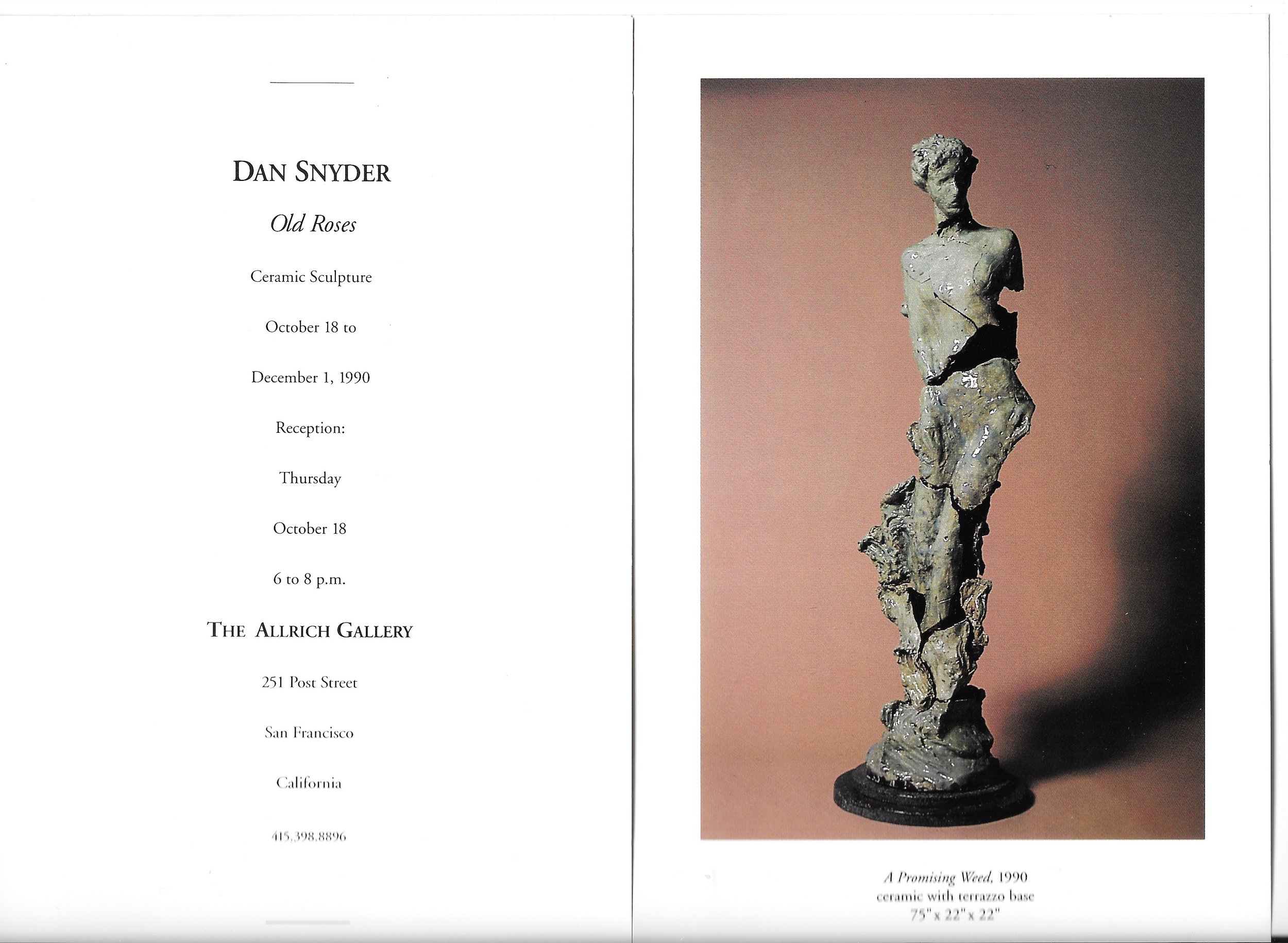

An exhibition of ceramic figures reminiscent of the sculpture of ancient Mediterranean civilizations byCalifornia artist Dan Snyder, was on view at the Allrich Gallery in San Francisco through December 1, 1990.

"There are two main themes for this body of work." Snyder commented. "The first, and to my mind the overriding one, is the physical nature of the medium itself.

What exactly it takes to move large masses of clay around--to cajole it into textures, patterns and colors, to really work with its natural tendencies toward cracking and breaking--has been of concern.

"The second theme, and probably the more visually apparent one, relates to the communicative life of the figures. Rather than emphasizing new ideas, my work tends to reveal forgotten feelings, stories or symbols. Beauty and magic--that which is un- earthed or rediscovered in some way have long been what I hope to find and share through my work. Clay lends itself well to my process, which I feel is more akin to digging or mining for lost but dimly re-membered treasures, rather than creating new ones.

"With the title 'Old Roses; I hope to evoké memories of angels, spirits and guardians--long shrouded in vines and brambles; lost in a secret garden."

#3 of 3

DAN SNYDER

by Charles Shere

It has been five years since Dan Snyder's last solo exhibition, also at The Allrich Gallery, in the meantime his work has evolved subtly but considerably. Happily, the needs and appetites of our society for art have evolved in a congenial direction. This work would have been as beautiful a few years ago; as rewarding and inspiring to contemplate; but we would perhaps not have been as ready for the timeliness of its timelessness. For all the excesses of postmodernism there is a postmodernist truth: we need now to look past the new and the contemporary toward the basic and universal. Snyder's sculpture embodies chis urge. His subject - the human figure, already symbolic of the universal while emblematic of the individual - combines to a rare degree with his medium - clay, from ancient times the symbol of fluidity, change, fragility - and yet also of durability.

A large part of the success of this combination of subject and medium is due to Snyder's technical expertise, and to the unique method he's worked out. His technique is assemblage, that classical modernist sculptural procedure. He puts together fragments and details to build the final work. But the fragments themselves are produced from wet clay, pressed into plaster molds taken from earlier full-scale sculptures themselves modelled in wet clay. The technique evolved from the need to make big sculptural pieces - big enough to carry detail, big enough to have presence; yet too big to fire, to move around, perhaps even to sustain their own weight.

This technique explains Snyder's success only partly. Greater credit must go to the vision that is expressed through the technique - a vision that also very likely led to its development. Just as these figures emerge from their bases, through improbably slender stems - like gracefully arranged bouquets of flowers emerging from carefully chosen vases - so Snyder's work emerges from its medium. In a new and curious way, the medium of clay is re- dedicated to the expression of fugitive ecstasy. It's appropriate that he has turned from the orldly athletes of carlier exhibitions to these angels, creatures not of fiction but of promise beyond the mundane. It's not surprising to find that Snyder was inspired, while at the American Academy in Rome some years ago, by life-size Etruscan ceramic sculpture: figure with similar inscrutable joyousness.

But they are not simple quotations, or pastiche, or ponderous allusions. Like any accomplished art, these figures know and refer to their predecessors, nod to their contemporaries, and focus their vision on something beyond routine human experience; something which is not so much private and their own (which would be mere obscurity) as it is reserved for future revelation and hence inexpressible. (This may be at the core of a curious paradox: that the meanings of works of art, which are always so expressive themselves, remain ineffable.)

It may be that in remote antiquity this vision (and its objects) was more generally known and acknowledged, and that the rapid development of conscious thought and consequent sophistication was achieved at the cost of suppressing and forgetting it. Dryads, once universally recognized, have been imprisoned by arboriculturists; naiads, by hydraulic engineers. Snyder recalls these graceful spirits, but with gestures, materials and awareness appropriate to our own time. The proof can be found in the relevance of his work to that of slightly older contemporaries: Manuel Neri, Stephen de Stabler, Nathan Oliveira. Like them he has learned from a variety of Modernist masters: among others Marini, Giacometti, Degas (whose sculpture must be counted a Modernist source). Like them he has adapted the lessons to two ends: the development of his own personal style and the expression of the needs of his own time and place.

The distance between his earlier work, exhibited here in 1982, and the present work, indicates considerable development in these two areas. In a sense he has returned to the frankly humanist expression of work he made as a graduate student at Davis. But that early work was much more beholden to Neri and de Stabler. He overcame those influences by developing new imagery (especially by relying on a kind of celebration of virility, no bad thing itself; and especially by developing the technique already described. Now, though, secure in that technique and in the truth and strength of a maturer, less mannered outlook he has returned to his instincts. In doing this I think he has brought unusual contemporary energy and life to an improbable area, figurative sculpture; and in doing that he has accomplished an important and significant thing: restoring figurative sculpture as a viable medium for contemporary art.

It remains to be seen whether he has done this at the cost, perhaps, of his own stature as a serious artist. For this is subtle, self-effacing sculpture; it doesn't cry out for attention. (If this is a reason some would argue Snyder's work is not Modernist, it is also also a reason it cannot be postmodernist.) It is easy to look at. It decorates its space beautifully. But, like a household art of the Etruscans, of the citizens of Pompeii, of the Egyptians, it will continue to please and refresh its connoisseurs, while encouraging them to reflect on the human condition. And that, ultimately, is, to a considerable degree, the purpose of art.

Charles Shere, September 1990